NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

Scientists have created a new antibody treatment that helps the immune system recognize and attack pancreatic cancer.

Pancreatic cancer cells use a sugary “disguise” to trick the immune system into ignoring them.

Most current cancer immunotherapies target proteins or genes, but this new therapy focuses on the sugars on the cell surface, blocking them so that immune cells can find and attack the cancer, according to researchers from Northwestern University in Chicago.

CANCER VACCINE SHOWS PROMISE IN PREVENTING RECURRENCE OF PANCREATIC, COLORECTAL TUMORS

“Pancreatic cancer is notoriously good at hiding from the immune system, but we were struck that a single sugar, called sialic acid, can so powerfully fool immune cells,” senior author Mohamed Abdel-Mohsen, associate professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, told Fox News Digital.

“When tumors sugar-coat themselves with this molecule, it flips an immune ‘off switch’ on certain immune cells, essentially signaling, ‘I’m a normal, healthy cell; don’t attack.’”

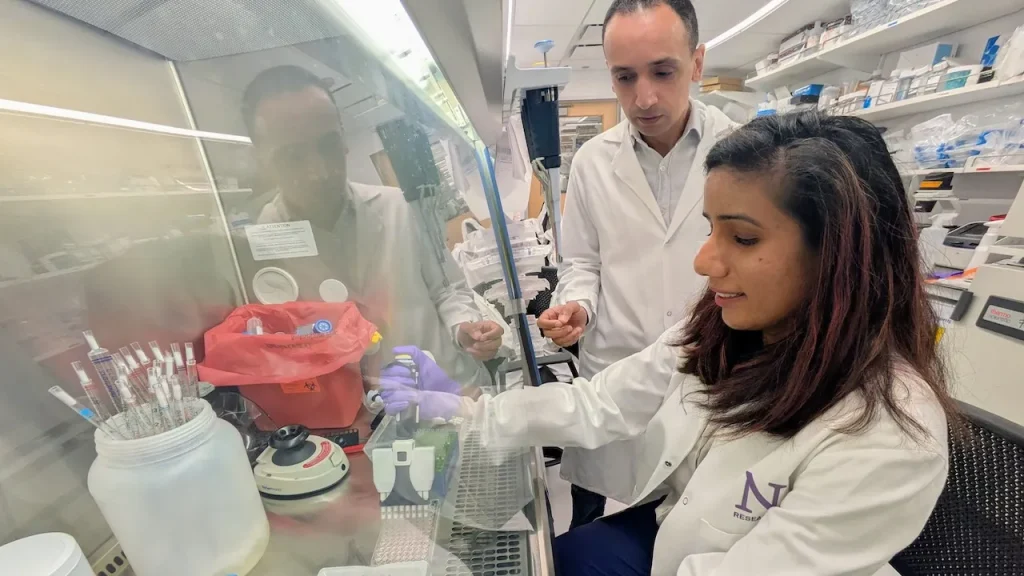

Study authors Mohamed Abdel-Mohsen (top) and Pratima Saini (foreground) are pictured in Abdel-Mohsen’s lab. (Northwestern University)

In mice studies, the therapy was shown to be successful in blocking this sugar signal, “waking up” immune cells and slowing cancer’s growth.

In two mouse models, tumors treated with the antibody grew significantly slower than groups that did not receive the treatment, the study showed.

CANCER SURVIVAL APPEARS TO DOUBLE WITH COMMON VACCINE, RESEARCHERS SAY

These findings could pave the way toward testing in human groups, and could potentially be combined with chemotherapy and existing immunotherapies, according to the researchers.

The findings were published in the journal Cancer Research on Nov. 3.

Study senior author Mohamed Abdel-Mohsen is shown in his lab. “This is early-stage, preclinical research, not a treatment today, but it opens a new immune target in pancreatic cancer,” he said. (Northwestern University)

“This is early-stage, preclinical research, not a treatment today, but it opens a new immune target in pancreatic cancer,” said Abdel-Mohson.

Heloisa P. Soares, M.D., Ph.D., medical director of theranostics at Huntsman Cancer Institute and associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Utah, said this research is “encouraging” because it points to a new way of helping the immune system recognize and fight pancreatic cancer.

“Pancreatic cancer is notoriously good at hiding from the immune system.”

“It was surprising to learn that a protein usually responsible for helping cells stick together is also being used by pancreatic cancer as a hidden ‘do-not-attack’ signal,” Soares, who was not involved in the study, told Fox News Digital.

“The striking part was that when this signal was blocked, the immune cells woke back up and started attacking the tumor much more effectively — which suggests a promising new direction for treatment.”

CANCER TREATMENT COULD BE LESS EFFECTIVE IF PATIENTS CONSUME POPULAR SWEETENER

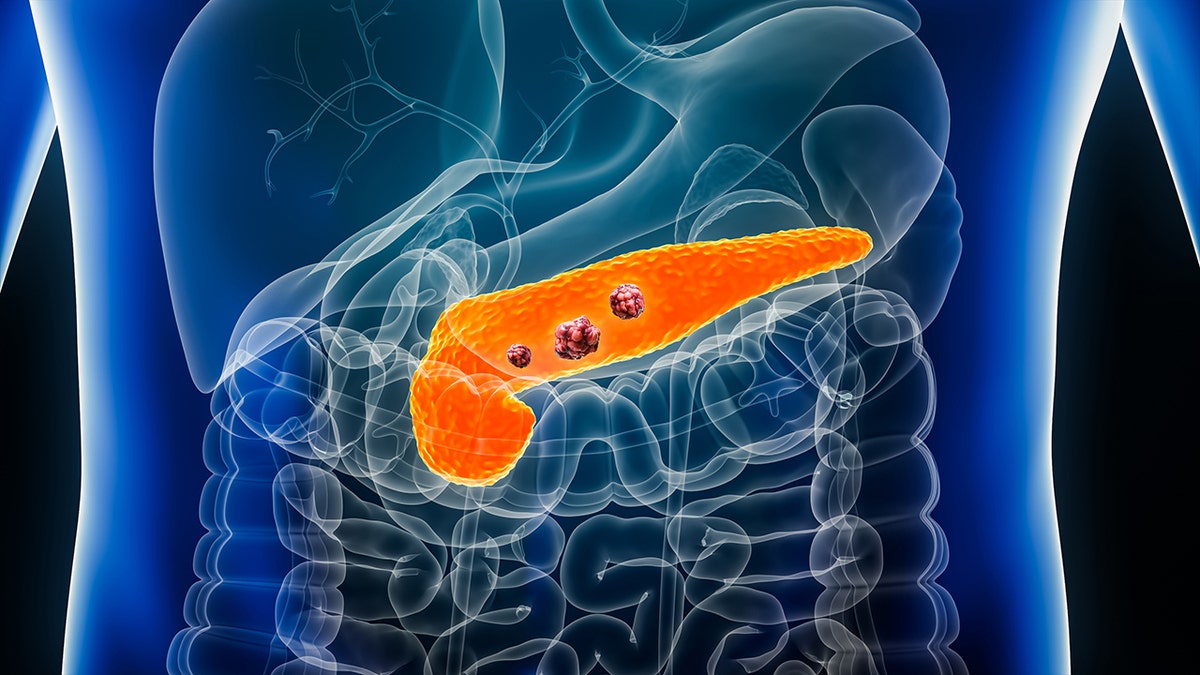

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most lethal forms of the disease. It’s usually detected at an advanced stage, leaving patients with limited treatment choices and a five-year survival rate of only about 13%, the researchers noted.

Unlike many other cancers, it often doesn’t respond to immunotherapy.

Pancreatic cancer is usually detected at an advanced stage, leaving patients with limited treatment choices and a five-year survival rate of only about 13%. (iStock)

“Pancreatic cancer is often diagnosed late, in part because it remains asymptomatic and is deep in the body,” Dr. Marc Siegel, Fox News senior medical analyst, told Fox News Digital.

“It is also difficult to treat because it doesn’t have many good immune targets and doesn’t mutate that much.”

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD THE FOX NEWS APP

The study did have some limitations, the researchers acknowledged — primarily that the tests have only been conducted on animals thus far and there is not yet any human data.

“Animal models cannot capture all the complexity of human pancreatic cancer,” the lead researcher noted. “Tumors also use multiple escape routes, so this strategy will likely be part of a combination approach.”

After human trials, the researchers estimate that it could take about five years before the therapy would be available to patients. (Northwestern University)

The long-term safety and dosing parameters of the therapy are also unknown.

“We need clinical trials to see how effective this is in humans and whether it has a role in cancer treatments for this difficult and deadly cancer — but it is quite promising,” Siegel added.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

The research team is now working with clinicians at Northwestern’s Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center on next steps toward potential human studies, likely in combination with current chemotherapy and immunotherapies, according to Abdel-Mohsen.

“It’s a promising step forward, but not something that will change care overnight.”

“If future studies support it, this approach could be added to the toolbox against pancreatic cancer, likely alongside existing chemo-immunotherapy, not replacing what’s working today,” he told Fox News Digital.

After human trials, the researchers estimate that it could take about five years before the therapy would be available to patients.

TEST YOURSELF WITH OUR LATEST LIFESTYLE QUIZ

Soares added, “It’s a promising step forward, but not something that will change care overnight. Continued funding and participation in clinical trials are essential to keep this progress moving.”

CLICK HERE FOR MORE HEALTH STORIES

The study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health.