CNN

—

The disarray in Donald Trump’s foreign policy team is mirroring the chaos and uncertainty that he’s foisted upon the world in the last three months.

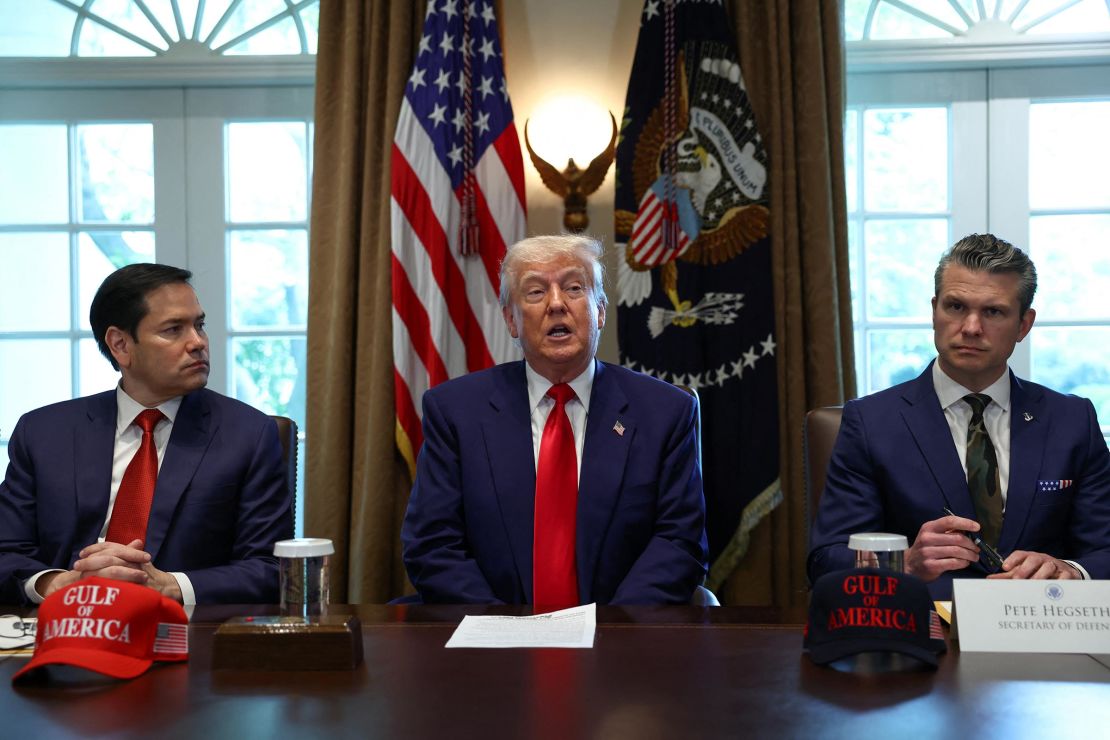

The president’s ouster of national security adviser Mike Waltz on Thursday and his decision to hand Waltz’s White House portfolio to Secretary of State Marco Rubio comes at a fraught moment in international relations.

The trade war that Trump ignited with China is beginning to damage the economy with no easy way out. The administration’s drive to forge peace in Ukraine is yet to bear fruit. And American soft power has been hamstrung by Trump’s attacks on allies and his throttling of US aid.

But Rubio’s most exacting challenge will be at home.

And even if he does a great job, it’s unlikely he’ll be able to impose much coherence on US foreign policy. That’s because the most — and perhaps only — important influence on the America’s global role is Trump himself.

The president is unpredictable, volatile and determined to pursue policies that subvert the principles of US global leadership that have been ingrained since World War II. He cozies up to authoritarians, threatens to annex territory of NATO allies and treats foreign policy more as a giant real estate deal than statecraft. That’s one reason why his envoy Steve Witkoff, a real estate mogul, is handling talks on Ukraine, the Middle East and Iran — a role that has already raised questions about Rubio’s influence over foreign policy.

The whole point of Trump’s approach is not to send the world a message that the US is a stable, consistent power that can be relied upon. This is what his voters — who bought into his claim that the world has forever been ripping off the US — wanted.

The best case for this erratic approach was made by Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent on ABC News’ “This Week,” speaking about the president’s trade escalation on China: “In game theory it’s called strategic uncertainty,” Bessent said. “So, you’re not going to tell the person on the other side of the negotiation where you’re going to end up.”

Trump’s critics have another description for it: total chaos.

Further complicating Rubio’s position is that any policy pursued by Trump’s subordinates can be blown up at any moment — as his first-term national security team discovered. The idea that officials serve at the pleasure of the president has never previously come with such a guarantee of impermanence. His ad hoc leadership was underscored Thursday when Tammy Bruce, the State Department spokeswoman, was informed of her boss’s new responsibilities by CNN’s Kylie Atwood during a briefing.

All of which is to say that Rubio faces huge challenges as the first official to serve as both secretary of state and national security adviser since Henry Kissinger — and doing so under a president whose foreign policy is an extension of his volatile personality.

Still, there are signs that the former Florida senator and 2016 candidate for the GOP nomination has forged a workable relationship with the president. As Rubio visibly sank in his chair during the extraordinary dressing-down Trump administered to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in their notorious Oval Office meeting, many foreign policy observers thought that he might be the first foreign policy big dog to leave the administration.

But he’s still there — and getting more responsibility.

One key to Rubio’s success so far is his willingness to lavish praise on Trump almost every time he’s in front of a camera. He repeatedly stresses that the president is calling the foreign policy shots and his job is to implement his boss’s wishes.

“This president inherited 30 years of foreign policy that was built around what was good for the world,” Rubio said in front of Trump at a Cabinet meeting on Wednesday. “In essence, the decisions we made as a government, in trade, in foreign policy was basically, is it good for the world? Is it good for the global community? And under President Trump, we’re making a foreign policy now that’s — was it good for America? …. Does it make America stronger? Does it make America safer? And does it make America richer?”

Such positioning is fine at home in the US. But when Rubio goes on the road — in a world that is conditioned to expect US leadership, not provocations — he is inevitably confronted with awkward moments. He was, for instance, asked by reporters to explain the president’s demands for Canada to become the 51st state while on Canadian soil.

This is a notion that would have been regarded as absurd and insulting by any previous modern US president. Given the traditional conservative ideals Rubio once espoused, it would have been to him as well when he served on the Senate Foreign Relations and Intelligence Committees. But Rubio didn’t risk getting crossways with a president who sees everything on cable TV. “There is a disagreement between the president’s position and the position of the Canadian government,” Rubio said, somehow implying that Trump’s stance was legitimate and not one of the most outlandish threats in modern US history.

Rubio’s embrace of Trump’s “Make America great again” dogma has dismayed some of his former Senate friends, especially Democrats, who voted along with Republicans to confirm him as secretary of state 99-0. But no one who watched Rubio’s speech at the Republican National Convention last year — and his embrace of the opponent who called him “Little Marco” on the 2016 campaign trail — could have been at all surprised.

Rubio has real talent. As a young, politically adept Republican with Cuban immigrant parents, he was once seen as someone who could broaden the party’s appeal. But the party that he prepared for half his life to lead as a Florida legislator and senator — solidly in the robust Republican tradition of strong defense, support for allies, antipathy toward authoritarianism and support for human rights — no longer exists. This is why many of Rubio’s disappointed advocates in the political center believe he has compromised his principles for power, perhaps because of his unfulfilled presidential ambitions.

But Rubio’s conversion feels complete. He has been at the forefront of Trump’s attempts to use foreign policy to expand his own presidential powers and a key player in actions that test common interpretations of the rule of law. This is especially the case as he’s tried to boost Trump’s mass deportation program.

The secretary of state used controversial powers to detain pro-Palestinian protesters who took part in protests over Israel’s assault on Gaza following Hamas terrorist attacks in 2023. He has declared that many of those involved took actions that are detrimental to US foreign policy — a categorization that suggests almost endless scope to suppress speech among resident aliens that the government doesn’t like. Rubio maintains such protests violate prohibitions on students with US visas taking part in political activity in favor of groups like Hamas.

“We don’t want terrorists in America,” Rubio said on CBS’s “Face the Nation” in March. “I don’t know where we have gotten it in our head that a visa is some sort of birthright. … If you violate the terms of your visitation, you’re going to leave.”

Rubio has also been deeply involved in the case of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, an undocumented migrant living in Maryland who was deported to a notorious prison in his native El Salvador despite a judge’s order that he not be sent there. He told reporters this week that he’d never say whether he’s spoken to Salvadoran President Najib Bukele about the case, following a Supreme Court ruling that the government must “facilitate” Garcia’s return.

“I would never tell you that,” Rubio responded to reporter who asked about a possible return of the man. “And you know who else I’ll never tell? A judge,” Rubio added, saying it was “because the conduct of our foreign policy belongs to the president of the United States and the executive branch, not some judge.”

It is that loyalty that appears to have endeared Rubio to Trump, and to have led to his latest promotion — even if he’s still regarded as an imposter by some sections of the MAGA movement.

“Marco Rubio, unbelievable, unbelievable Marco. When I have a problem, I call up Marco. He gets it solved,” the president said Thursday.

But everyone who serves Trump knows his faith can be fickle.

Rubio’s biggest job as the face of US diplomacy is therefore not preserving world peace, defusing a risky clash with China or keeping Americans safe. It’s making sure he doesn’t become a problem for his mercurial boss that even he can’t solve.