Marshall, North Carolina

CNN

—

Korey Hampton sees progress every day as she works along the French Broad River. But, nine months after Hurricane Helene, there are still painful reminders and flashbacks.

“I still see piles and I wonder if there is somebody in it,” Hampton said. “I still smell smells and think I should go look at that pile. It’s hard to switch back to the, ‘Oh, everything is fun. No big deal.’”

Hampton is trying. She and her husband, Mitch, own French Broad Adventures, an outdoor activity company that offers rafting, ziplining and more in Western North Carolina.

The river is her office, and her source of income and joy. Tourists are drawn here for the postcard views. The Appalachian Trail winds through the mountains above; the French Broad River below is a rafting and kayaking playground.

But the Hamptons are also volunteers for the local raft rescue squad. When the floodwaters came after the hurricane, it meant days of exhausting rescues. Then weeks of worse: recovering bodies.

“It painted the river in a new light for me, right?” Hampton said. “Normally, we are taking tourists out. Families, school groups, wedding parties. Everybody’s out here to have a good time. But for that amount of time I was here doing, we were all here, doing gruesome work. … So, I’m getting there, but it’s going to take a while.”

Hampton’s personal recovery runs parallel to the physical, financial and emotional challenge of getting the small towns devastated by the floods back to some new normal.

To visit is to see obvious progress. In downtown Marshall, for example, some businesses have reopened, and the steady sound of saws and hammers and drills tells you others are getting closer.

But the steep challenges remain obvious, too, no matter where you look. In the town, some buildings are still closed, still filled with dirt and mud, still waiting for an insurance check or government help or for their owners to decide if they can afford it or risk it happening again.

Along the river, there are still debris piles in harder-to-reach places, some of them carrying logos of businesses 20 miles or more upriver. We met Hampton at a rocky and sandy bend she said was lined with mature trees this time last year.

“The water came up 27 vertical feet,” she said. “That meant sometimes hundreds of horizontal feet where there was floodwater. So a lot of trees are missing, and the river feels a little bit wider.”

We visited as part of our “All Over the Map” project, an effort to track major events through the eyes and experiences of everyday Americans.

We were reminded, yet again, of the often-giant gap between what we see and hear on social media or in national political conversations and the views of those who live in the center — in this case literally — of the storm. The blame game and finger-pointing playing out now after the tragic recent Texas flooding is in many ways a flashback for residents of Western North Carolina.

Hurricane Helene made landfall in Florida on September 26 as a Category 4. It was the next day, September 27, that churning horror came to the small towns dotting the rivers and streams below the eastern facing slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

“The first call came in about 6:30 in the morning,” Hampton said. “We pulled people out of second-story windows in a river that just the day before was calmer even than it is today.”

Cellular service was lost. Radio communication was spotty. Saving lives and property was all that mattered. It would be days, sometimes longer, before locals could get online or hear from family or friends who lived elsewhere.

A lot of what they heard was from a parallel universe. It was a little more than five weeks to Election Day, and the internet swelled with misinformation. About the death toll. About the federal and state response. About just about everything.

CNN visits North Carolina after Hurricane Helene

Then-candidate Trump made a number of false statements about the Biden administration response. Among them: that President Joe Biden refused to call Georgia’s Republican governor; that FEMA was ignoring Republican counties impacted by Helene; and that FEMA lacked resources because Vice President Kamala Harris had directed FEMA funds be used to house undocumented immigrants. Trump and allies also reposted social media postings that were false

“We just didn’t have the time. People were literally dying,” Hampton said. “We didn’t even know what was happening until the first Black Hawk helicopter landed with water and food.”

The debate continues, at considerably less volume, nine months later. Then it was about Biden. Now it is President Trump at the center of questions about the pace and scope of federal help and the future of FEMA.

In the epicenter, where the pain and need are deepest, that conversation is remarkably calm and respectful.

“We’re not down here taking sides,” Hampton said. “We just wish somebody would help and that political wrangling over our futures would stop.”

The 2020 census put the population of Marshall at 846. Hot Springs, about 16 miles to the northwest, was listed at 520. All of Madison County — northwest of Asheville, where North Carolina meets Tennessee — is home to 22,000 people. Small towns like these are different. And full of lessons.

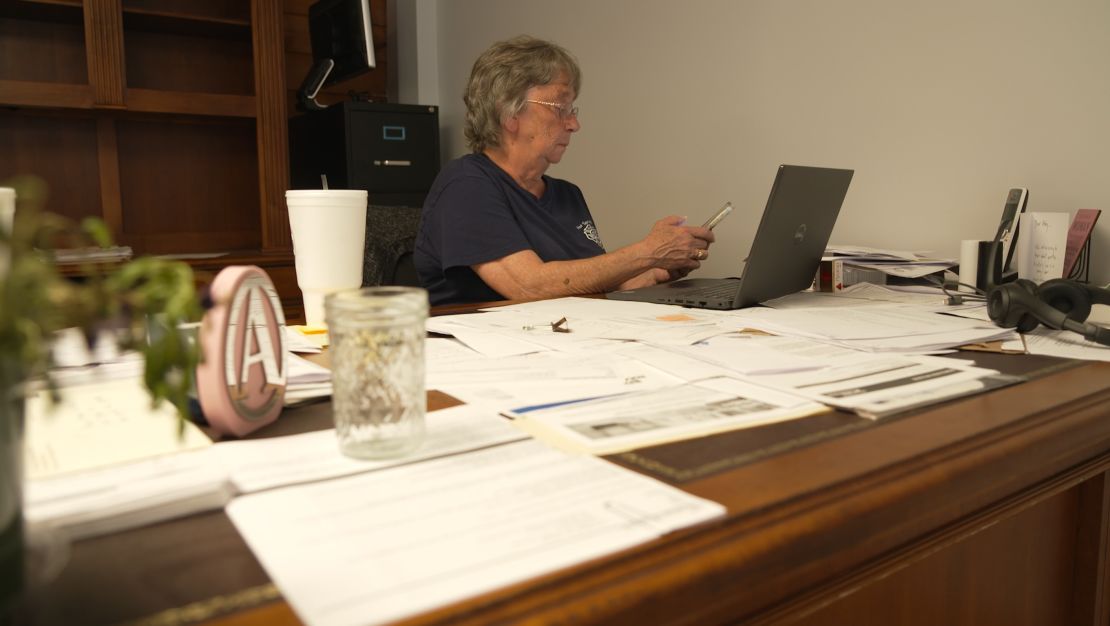

While Trump and his allies helped fuel the disinformation campaign after the floods, Amy Rubin wasn’t going to vote for him anyway. She is a Democrat in Hot Springs, in a county that voted 60 percent for Trump. But her disagreements with him aren’t related to disaster relief, so Rubin shares them with likeminded friends in private and then remembers what is paramount here.

“We, the community, we just tried to let all of that go and just help each other,” Rubin said. “And that’s what was great about it.”

Rubin and her husband own Big Pillow Brewing, one of the first businesses to reopen in Hot Springs. They are still waiting for a check from their flood insurance, but decided to press ahead with the cleanup and rebuild anyway.

An unpainted board across the bar inside marks how high the waters rose in the building. “About maybe thigh high,” is Rubin’s memory. The stage for music outside is all new lumber. The crowd on a recent Friday night was proof that locals and visitors are grateful for at least a taste of normal.

But it takes just a few steps to see the daunting work that remains. The building that housed the offices of the sheriff and mayor, as well as other town offices, is still a mess, though most of the mud has been shoveled from the basement. The hardware store is closed. So is the inn where Hampton made one second-story rescue.

The flood here was mostly caused when debris turned a bridge on the Spring Creek into a dam. Ask almost anyone here what still needs to be done, and replacing the bridge or significantly redesigning its support beams tops their long list.

“I don’t really know whose jurisdiction that is, but it is definitely something that needs to happen,” Rubin said. “Because, you know, people are saying this is going to happen again.”

Hot Springs Mayor Abby Norton met us after taking her first days off since September 27.

“A little recharged,” she said with a smile and laugh. But now she’s back to work. “I would say we are only about 40 percent back.”

Norton’s initial expectations turned out to be unrealistic.

About how long it would take: “I was thinking months. … At the time, you are just not thinking clearly to see all the damages. We still got a year, two years before we are back.”

And about who pays: “What I thought Washington would do would be to immediately come in and either fix everything or supply the funds for us to fix everything. But that is not how it works.”

Norton now knows things she wishes she didn’t about FEMA rules and environmental studies and other bureaucratic hurdles. And she knows some in her community might disagree with her take on Washington’s role here.

Some context first: Mayoral elections here are nonpartisan. Norton is a Christian who says prayer guides her every big decision. She says she voted third-party in November — just after the flood — because she couldn’t bring herself to support either Trump or Harris.

Her take: “I’m not a politician. I never have been. But it has been better under the Trump administration than it was under Biden. My opinion.”

Still, she says things take too long — like getting a federal check to repair the town offices. And she is troubled when she hears Trump and his team talk about eliminating FEMA or dramatically shrinking the federal role in disaster relief.

“FEMA doesn’t need to be eliminated,” Norton said. “The processes need to be easier, more user friendly. No, I don’t think it needs to be eliminated at all.”

Or its functions shifted to the states?

“No.”

To live in a river town is to know the waters will rise now and then, that you better keep sandbags handy and think twice about how you furnish the first floor.

But it is nearly 500 miles east to the Atlantic Ocean from Marshall; more than 500 miles south to the coast along the Florida panhandle. Madison County was not a place on any hurricane watch list.

So when Josh Copus woke up early on September 27, he was thinking about sandbags and moving some valuables up to the second floor of his Old Marshall Jail Hotel. Plus, moving or securing the furniture on the restaurant patio that abuts the railroad tracks along the French Broad River.

“I knew it was going to be bad, but I was, like, ‘We got this,’” Copus said. “And at 9 o’clock, the water went over the railroad tracks, which hadn’t happened since ’77. In an hour, there was 4 feet of water in the town, and you could just immediately know this was a different kind of event.”

He went to the top step of the Madison County Courthouse, the highest place with a view of the river and his hotel. But after two hours watching, he had to flee: The water was rushing up the steps and into the courthouse. At the peak, it surged 27 feet up the flood ruler painted on the side of the old jail Copus had painstakingly restored as a hotel and gathering place.

“The first phase is shock,” Copus said. “Just feeling like floating outside of my body.”

He thought the town was finished, and business with it.

“In that moment? 100 percent,” Copus said. “We were alone. There was no cell service. … And you are in that space, and you are looking at that destruction and it feels like you are done.”

But Copus headed to town early Sunday anyway and realized there was one thing the flood could not break.

“No one could talk to each other,” Copus said. “But we all just had the same idea. I guess we just go to town. And everyone went, and we just started. Started with shovels. Dump trucks came. Backhoes came. Neighbors brought things. I saw a woman walking into town with a mop. Just walking into town with a mop. And I was, like, ‘you go, girl.’ Bring it. Whatever you got.”

“And we didn’t wait on anyone to save us. We just started. And that was the moment. … I changed the way I was speaking about it, and I said, you know, our buildings were destroyed. Our town is not the things. It’s the people. And the people are still here. And we’ve got the best people.”

Copus was still shoveling when Election Day came, but he took a break to vote and encountered the parallel universe.

“I remember standing in a line and this woman, you know, from our community, was like, ‘I heard FEMA condemned Marshall.’ And I was like, ‘I just came from there. Like no, we’re coming back.’ And she was like, ‘I saw it on the internet.’ …. That stuff is hard, but it is the world we live in.”

But it is different here.

No one shoveling mud asked anyone whom they were voting for or whether a Democrat or Republican owned that building or business.

Now, getting new pipes and bridges and things like the railroad crossing fixed are challenges for everyone in Marshall and Hot Springs.

“It’s not like everyone is walking around with a blue hat or a red hat,” Copus said. “We’re just people down here. And some of the beauty of the flood was how it really taught us that, again, we have more in common than we have that separates us.

“We’re all Appalachian Americans. That’s something that we can all connect with. So regardless of your political affiliation, our culture connects us for sure. Our values systems are actually not that different.”

To hear the words “beauty of the flood” from Copus is telling. He is a potter, a gifted ceramics artist with a studio and kilns in the woods outside Marshall. He organized musicians to record an album at the hotel in the middle of the restoration work. The proceeds will help the recovery.

“I’ve been looking for silver linings the whole time,” said Copus. “This is a terrible deal and it’s not the deal any of us wanted. But it’s the deal we got. Sitting around and feeling sorry for yourself isn’t going to help. I think artists are really good at trying to see beauty within the darkness. And that’s what I have been trying to do.”