New York

CNN

—

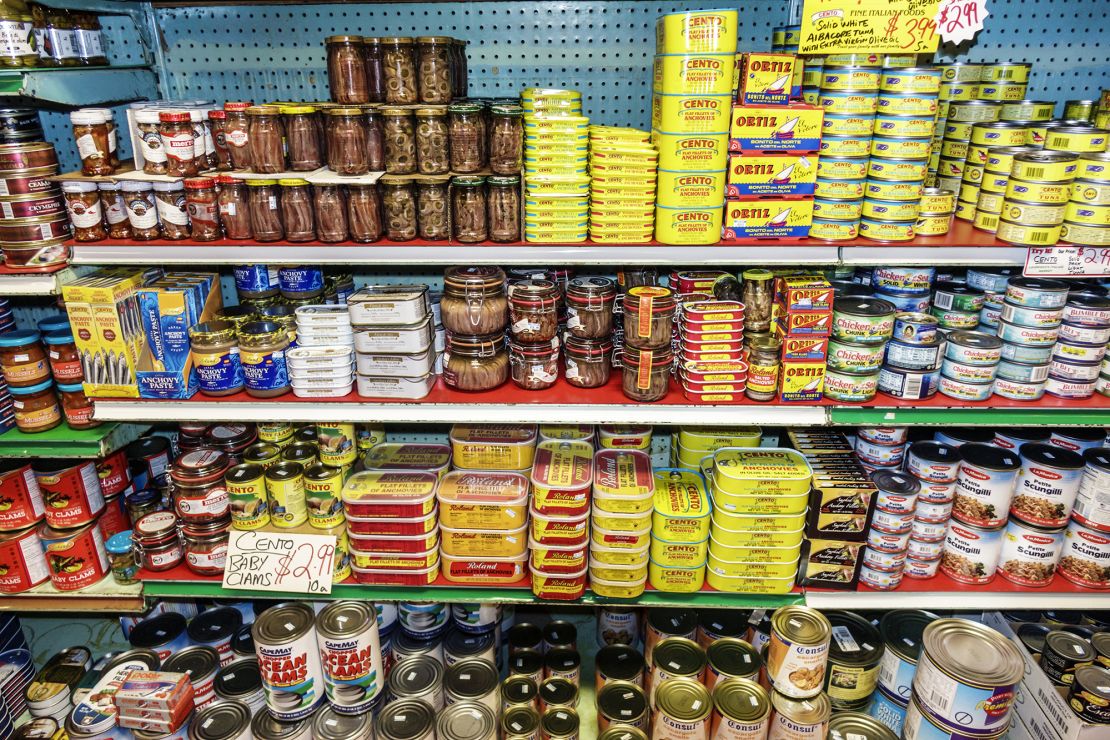

Tinned fish in America no longer means a sad, forgotten can of tuna collecting dust in the pantry. And Americans looking to save money in the face of economic headwinds are fueling their soaring popularity.

Social media users are proudly posting a mosaic of gourmet ocean-dwellers plucked from waters off the coasts of countries like Spain and Italy, with vibrant packaging that evokes a Mediterranean seaside vacation. Try a lemon caper mackerel over poached egg and toast, or chop up spicy sardines over bruschetta and balsamic, they encourage. Even Trader Joe’s, long a mainstream cultural bellwether, makes a surprisingly flavorful canned calamari.

Social butterflies are hosting tinned fish parties, while those who want a chill night in are creating “seacuterie” boards – like charcuterie boards but with tinned fish – or whipping up gourmet pastas with a $4.99 can of sardines.

Tinned fish, unlike toilet paper and dalgona coffee is one of those pandemic purchases that has had relative staying power in the American psyche. But chatter about tinned fish has particularly spiked in recent months, at the same time as economic anxiety and declining consumer sentiment amid the Trump administration’s chaotic trade war.

Though the United States isn’t in a recession right now, economic optimism is at a near-record low, according to University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index this month. It’s a sign that tinned fish could be a grim “recession indicator,” some social media commentators – and experts – lament.

Searches for “tinned fish” on Google spiked to the highest 2023 levels around the holiday season in 2024 and maintained an uptick since then. In the past 90 days, searches for Nuri’s Portuguese sardines in spiced olive oil skyrocketed 2,750% and Brunswick sardines in olive oil jumped 4,000%.

When you want to feel fancy, tinned fish is a “happy medium between a can of Bumble (tuna) and going to the fresh case in the grocery,” Chris Sherman, CEO of New England-based Island Creek Oysters, told CNN.

Consumers are looking for “affordable escapism,” Ross Steinman, a consumer psychologist and professor at Widener University, told CNN. Americans may not be traveling as much this summer. So instead of booking that trip to Mallorca, they’re sampling tinned fish imported from Spain in colorful Mediterranean-blue packaging.

Whether it’s a straight recession indicator is complicated, Amelia Finaret, a food economist at Allegheny College and registered dietician, said to CNN. If only cheap cans of tuna were increasing in popularity, that would be an alarming sign. The growth of both affordable and artisanal cans of sardines and mussels could just show Americans are diversifying their preferences for healthy sources of proteins.

However, she said when people are stressed out about the economy, they turn to two types of foods at the grocery stores: ones with a long shelf life and ones that are convenient, both qualities that tinned fish possess.

“If convenience is really what people are looking for, then maybe this is an indicator of strain, versus being able to spend time in the kitchen with fresh fish,” she said.

Tinned fish swims mainstream

And there’s no escaping sardines, even if the salty snacks aren’t your thing: Fashion bloggers predict it’s going to be a Sardine Girl Summer.

Anthropologie storefronts in Manhattan last month were adorned with human-sized decorations that looked like fish tins, and the retailer recently dropped a new collection that features sardines on glassware, towels and even candles – the $26 Original Tinned Fish Candle comes in a “tin,” with scents like olive oil and sea salt. Fashion retailer Staud’s beaded “Staudines” bag was on many a whimsical fashionista’s wish list.

The trend is similar to a luxury brand, Widener University’s Steinman said. But while luxury brands symbolize wealth, donning a sardine tote shows “you’re on the pulse and are aware of what’s going on.”

Island Creek Oysters began selling online in 2019, and it has “continued on an upward trend ever since,” Sherman said. Tinned fish was a way to bring restaurant-level food to your kitchen, he said, and the years-long shelf life also evoked the doomsday prepping sentiment that overtook some during the pandemic.

The growing tinned fish industry is still the “wild west,” said Dan Waber, co-owner of Rainbow Tomatoes Garden, a retailer of tinned fish. In niche industries like tinned fish, he notices even a good football game over the weekend or a post by a social media influencer can impact short-term sales.

Neah Patkunas, who reviews tinned fish on her Instagram, first got into the canned creatures in 2021 and was known in her circles as the “tinned fish girl.”

People thought it “kind of strange that I was eating it as frequently as I did,” she said. For Patkunas, tinned fish is a cheap and easy source of protein, but at the same time, she considers the pricier tins from Europe to be a luxury import.

Spain and Portugal are renowned for their tinned fish exports, and Northern Europe has a strong history in canning. Tinned fish industries are also strong in Japan, Korea and China.

And that could be making it harder for those who sell tinned fish in the US to plan ahead, since most fish in the US is imported.

Tariffs have thrown many businesses that rely on imports into a loop and put a damper on consumer sentiment. With the back-and-forth on tariffs, Waber hasn’t been able to make any major decisions on the imported goods.

“All we can do is react,” he said. “When the price goes up, the price we sell for goes up.” At the same time, a wide price range of tinned fish means that consumers can buy a $6 tin of sardines instead of a $10 one, he said.

Patkunas, the tinned fish reviewer, said Americans are late to the party, only now viewing tinned fish as a way to try another country’s delicacy. It wasn’t until late 2024 that her friends began viewing tinned fish as a new delicacy, and this year, she finally feels like “it’s something that I don’t feel weird bringing up.”

The few canneries based in the United States are enjoying the rise in popularity among Americans.

Mathew Scaletta’s grandmother started Wildfish Cannery in 1987 in southeastern Alaska. The business began as a stop for fishermen to have their catches smoked and preserved, open for just the few months of the summer fishing season. Then in the 2010s, Scaletta wondered why there wasn’t a cannery in the US that treated tinned goods like a delicacy with the best quality fish instead of a bare-bones commodity.

Ten years ago, he came back to Alaska and took over Wildfish Cannery with that vision, developing product lines and redesigning packaging. Once the first pandemic lockdown happened, “we sold what would’ve been months’ worth of stock in a week.”

He predicts that in five years, the US market will view tinned fish as more established, rather than a trend.

Five years after the pandemic, he still expressed surprise that the food he grew up eating over rice and hot sauce has become so trendy. But is tinned fish’s resurgence truly a recession indicator?

“I’m here selling $10 cans of fish, which is bougie as hell, so I don’t know,” he said.