CNN

—

It’s called a chicken tax, but it’s levied on pickups. And it shows just why President Donald Trump’s tariffs could change the US economy longer than you might think.

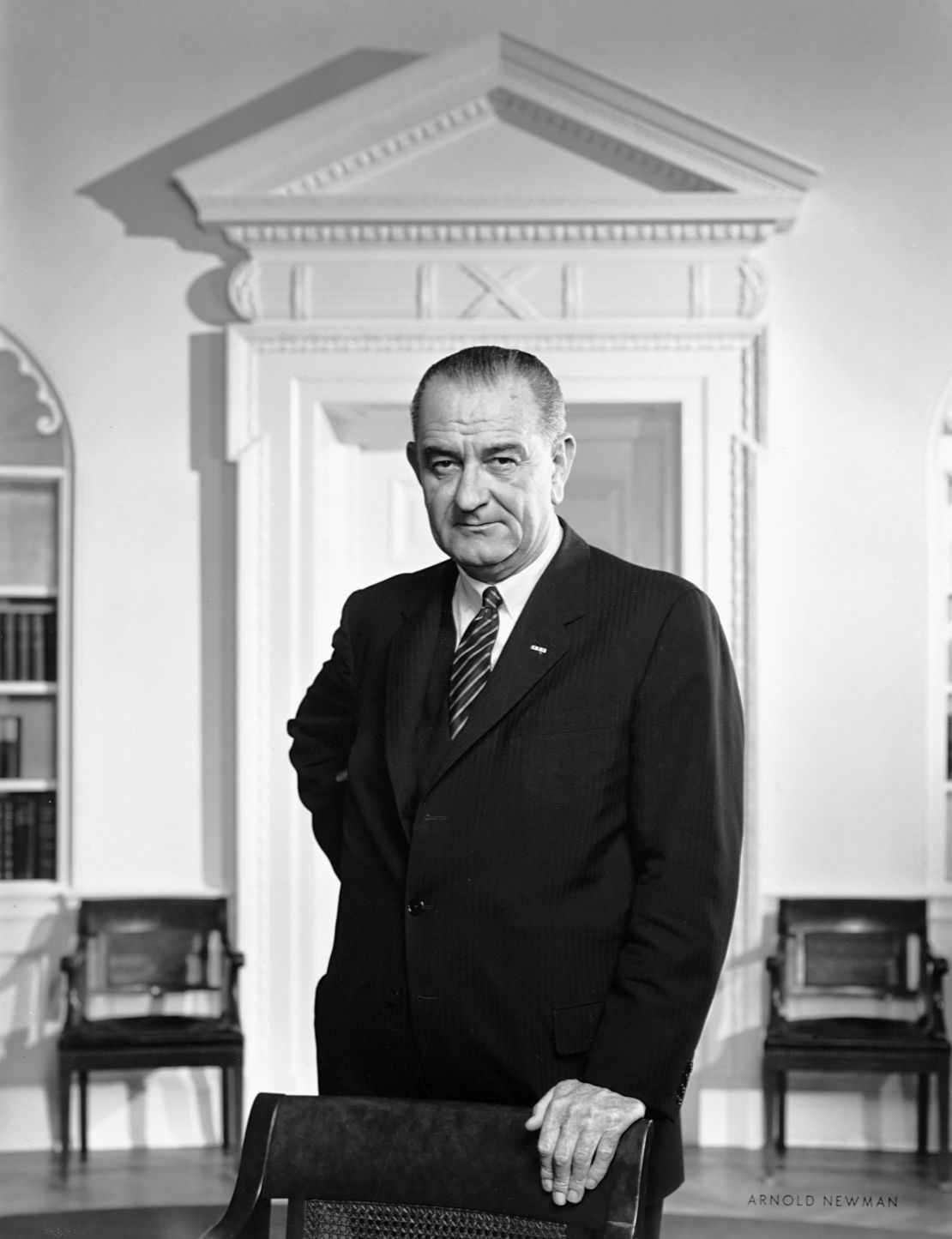

President Lyndon Johnson imposed the chicken tax in 1963, but it’s still in effect today, even though its supposed reason for existence is, well, no longer in existence.

The import tax’s longevity, though, underscores how tariffs can reshape global markets, sometimes well past the conditions they were put in place to address. Trump’s trade war could change the way Americans and the world shops and buys for generations to come.

To this day, the chicken tax essentially prevents automakers from selling pickup trucks made in Europe or Asia in America. Most US pickups are built in North America, leading to massive profits for US automakers but less choice and higher prices for millions of American buyers, as well as some impressively convoluted maneuvers by automakers to try to get around the tax.

“Trump seems to think he can announce very high tariffs and then them dial back. But tariffs changes economic incentives,” said Dan Ikenson, an economist and former director of international trade at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. “Constituencies develop and they take on a life of their own, and that’s why they’re long lived.”

The chicken tax started, unsurprisingly, with chickens.

In 1962, European countries tariffed American chicken, practically shutting US poultry producers out of the lucrative and growing market in Europe.

Soon after Johnson took office in 1963, he imposed “retaliatory” tariffs on a number of European products, including trucks. At the time, only a sliver of US car sales were imports and few Americans had even heard of Toyota or Honda.

The 25% tariffs on “motor vehicles for the transport of goods” was primarily to punish German automaker Volkswagen, which was the only foreign automaker making inroads into the US market at that time. There were also US tariffs on potato starch, dextrin and brandy, three other products important to European exporters. But the American beneficiaries of those tariffs didn’t have nearly the political clout as the auto industry, Ikenson said.

By cutting out foreign competition, the chicken tax opened the door for America’s “Big Three” automakers, General Motors, Ford and Chrysler, to raise prices on their trucks. Prices of American built trucks, though not subject to the tariffs, rose about 5% to 6% a year while car prices rose only 2% a year, according to preliminary analysis of car and truck prices by Jonathan Smoke, chief economist at Cox Automotive.

Bigger profits meant US automakers focused more on producing trucks. So even when Europe dropped the tax on American chickens in 1964, the Big Three and the auto workers union flexed their considerable muscle to keep the imports on foreign trucks in place, Smoke said.

“It was never challenged or questioned politically,” said Smoke.

Few, if any, truck buyers realize the tax meant they were paying higher prices, Smoke added. And since it spurred American production, “the average American would say this isn’t a bad thing.”

The chicken tax even survived numerous rounds of global trade agreements aimed at promoting free trade, including the creation of the World Trade Organization in 1995.

That’s because once the tariffs are in place, they tend to stay in place, says Lawrence Friedman, a global trade attorney. For example, there are still tariffs on televisions with cathode ray tubes – the big, bulky kind that have fallen out of favor in place of flatscreens – and ones with built-in VCR players.

But with trade restrictions comes the search for loopholes.

Such practices are common in the complex world of trade rules and tariffs, said Friedman. The term in the trade industry is “tariff engineering.”

To get around the chicken tax, some foreign automakers shipped trucks to the United States without the truck beds attached to the chassis. Others added extra seats so that the trucks were classified as passenger vehicles. The Subaru BRAT added two rear facing seats in its truck bed.

And it wasn’t only the foreign automakers who played games to avoid the chicken tax. Between 2009 and 2013, Ford, which was building the Transit Connect van in Europe, shipped them to the US with additional seats that would be removed once they cleared customs. The Department of Justice eventually fined Ford $365 million in 2024 over the issue.

However, it was the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA, that really opened a legal route around the chicken tax.

NAFTA opened the trade borders with Canada and Mexico, so automakers were soon building trucks destined for the US market both north and south of the border. General Motors, for example, builds its best-selling truck, the Silverado, in Canada and Mexico as well as the United States.

With pickup imports taxed, many Asian and European automakers turned to a different (less-tariffed) niche: cars. Especially smaller, more fuel-efficient economy cars.

The timing was on their side. With gas prices rising in the early 1970s, Americans flocked to those kinds of autos. When foreign brands began building US plants, starting with a Honda plant in Ohio in 1982, they concentrated first on cars, not trucks.

However, foreign brands didn’t build US factories because of the chicken tax, but because it was cheaper to build closer to where the cars would ultimately be sold.

“The tariff is not that much of an inducer of foreign direct investment the way we thought,” said Ikenson. “There was a ton of investment coming in to produce cars, and the tariff on them was only 2.5%.”

Even with the combination of shutting out foreign pickups and Americans’ love of trucks, the Big Three’s overall share of the US auto market has continued to shrink these last 60 years.

By 2007, Asian and European brands captured a majority of US combined car and truck sales over the traditional Big Three automakers for the first time, according to companies’ sales reports.

Though the Big Three still dominate truck sales, they now only account for 38% of overall US auto sales, producing fewer vehicles at their US plants last year – 4.6 million – than the 4.9 million built by foreign automakers, according to data from S&P Global Mobility.

How Trump’s tariffs change the market, and how long they stay, is tough to say, said Cox Automotive’s Smoke.

But however long they last, the chicken tax shows that undoing tariffs is never that simple. And even when tariffs raise car prices and cost more auto jobs than they create, the idea behind them is a powerful narrative, Smoke said.

“I wouldn’t be surprised that this one example of tariff that Americans end up supporting,” he said.