CNN

—

Twenty-five years ago, in his pristine but sparse Manhattan apartment, viewers got ready with Patrick Bateman for the first time, meeting the often suited and sometimes blood-drenched fictional character through his intensive morning routine.

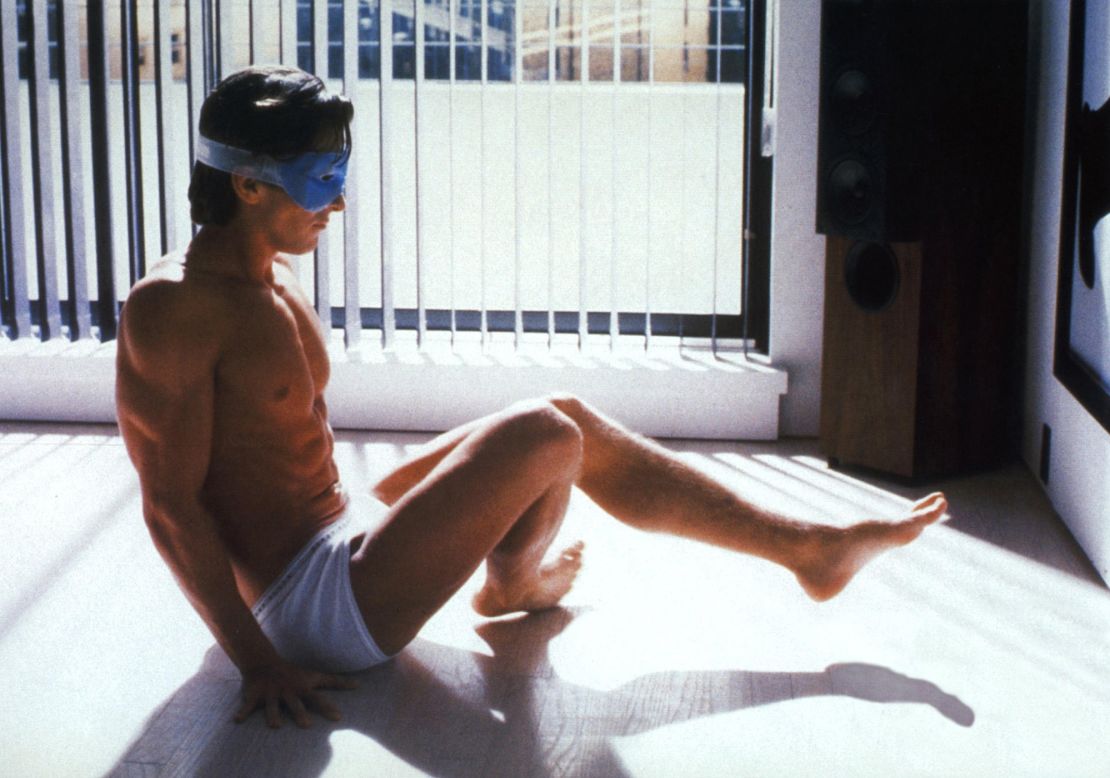

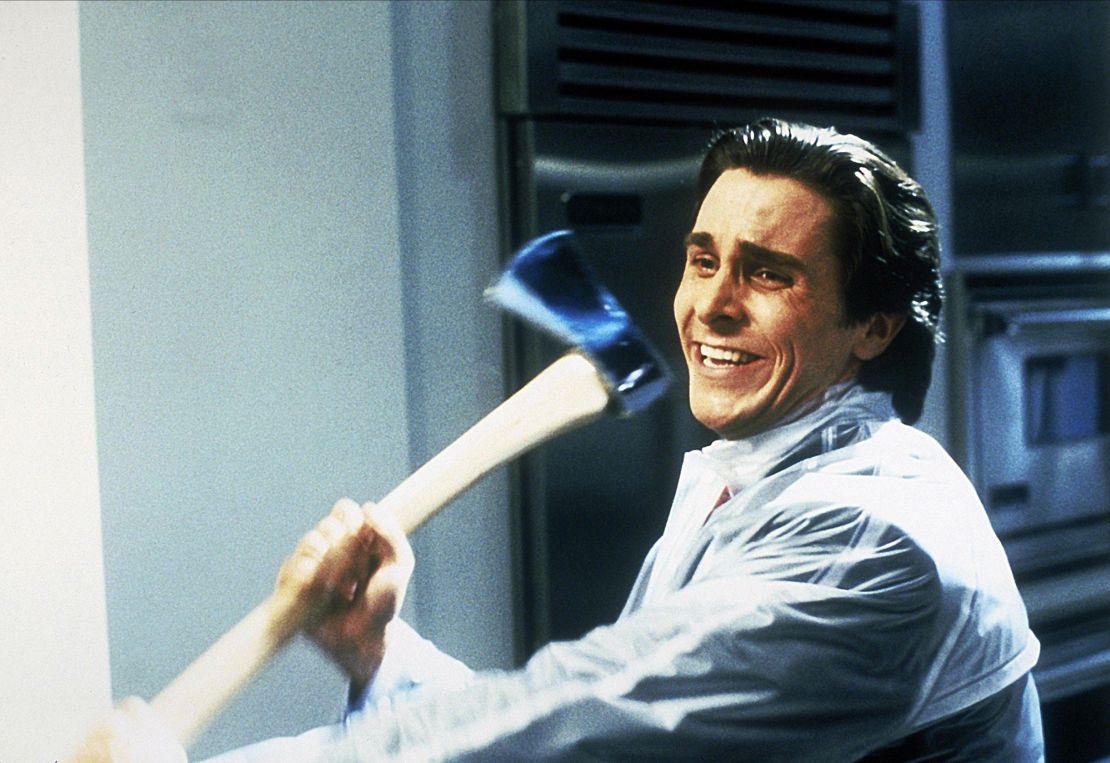

In the 2000 film adaptation of “American Psycho,” Christian Bale plays the yuppie investment banker — and nighttime serial killer, depending on your interpretation — who, upon waking, dons a cooling gel eye mask for his puffy eyelids while doing 1,000 crunches in his white briefs. He details his subsequent nine-step skincare routine at length with added pointers. (Alcohol-based products are drying and “make you look older,” he offers). When his glistening herb-mint facial mask peels off, his real mask slips, revealing his unsettling stare.

“There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me, only an entity, something illusory,” he monologues. “And though I can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable, I simply am not there.”

Throughout the film — and even more so in the book, published in 1991 by Bret Easton Ellis — Bateman is obsessive over brands and consumer goods, rattling off his knowledge and judging others on their tastes. Today, his specter lurks online through the hyper-consumerist attitudes on social media that almost makes his character’s obsessive behaviors seem normal.

Influencers chronicle their minute-by-minute early morning fitness and wellness routines or multistep nighttime skincare regimen that appear to involve a never-ending array of products. The “morning shed,” popularized on TikTok, can involve peeling off or discarding multiple hydrating skincare masks, wrinkle patches, chin straps, mouth tape, LED masks, hair rollers and body wraps, all apparently worn overnight, to start the day. (Last year, Allure called the trend “the prison of being perpetually hot.”)

“It’s a very relevant film for now, and of course, it was (released) way before social media,” said Jaap Kooijman, an associate professor in Media Studies and American Studies at the University of Amsterdam, who has written and taught on the book and film versions of “American Psycho,” in a phone interview. “But it’s based on the same principle of the outside appearance (and) consumer goods masking being empty inside.”

The film may depict a serial killer, but it’s the display of the “serial consumerism” of the era — then limited to traditional media like print and TV ads — that has become a fascinating harbinger as consumers’ aspiration for products that align with self-worth has only seemed to grow.

The film’s themes converge most directly in the “manosphere,” the increasingly persuasive corner of the internet pushing narrow and problematic views of masculinity. Bateman has often been held up as a cult symbol of the “sigma male,” an archetype for someone introverted and attractive who works hard, works out, has a good skincare routine, and also harbors contempt for women.

Ellis’ original intentions with his novel have been continually debated, with many critics believing the book to be inherently misogynistic. But director Mary Harron’s take on Bateman, co-written with screenwriter Guinevere Turner, has been considered feminist by some, including Kooijman, in its critiques.

“We’re still watching a serial killer, but it’s so over the top, and so well played by Christian Bale that it’s, you cannot take it fully seriously,” Kooijman explained.

The same can be said of engagement-baiting online, where every trend is taken to extremes and context can be lost. Is it satire when a six-hour morning routine goes viral for dunking one’s face in iced sparkling water at 5 a.m. after pushups on the balcony? Or does it only become that when someone else responds with their version dipping their face into the bowl with each push-up? Bateman may have taken notes and ditched his gel mask.

In any case, it’s all performance, something that “American Psycho” toes the line with as Bateman is increasingly revealed as an unreliable narrator. Bateman obsesses over the symbols of status — his business card typeface, the ever-elusive reservation at the notoriously exclusive restaurant Dorsia — but the reality of his day-to-day activities is unclear. His peers misidentify him, his outbursts to fiancé (played by Reese Witherspoon) and secretary (Chloë Sevigny) aren’t met with responses, and his chainsaw-wielding murders are cleaned up like they never happened at all.

“His persona as a serial killer is just as real — or not real — as his persona as a consumer and his persona as a (banker),” Kooijman said. “They become interchangeable, and that’s the terror, or the dystopian factor of ‘American Psycho.’”

Yet, while Ellis’ novel can be interpreted as a critique of the wealth and consumerism of New York in the ‘80s, a period of significant economic growth, it’s also presenting it, Kooijman said. “You could also read it as a celebration.”

Because of that, Bateman’s purpose may have been lost on the fans who could benefit from the film’s point. After all, by the end he is a pathetic figure, confessing his most depraved actions only to be called the wrong name and ignored once again (not so much a hero of masculinity after all).

Instead, many young men are circling around the same preoccupations that Bateman did, “looksmaxxing” to improve one’s jawline or skin but to an echo chamber of like-minded disaffected internet users, much like investment bankers showing off new business cards to one another to inflate their self-worth. The manosphere, after all, is intended for itself.

“You can always be thinner, look better,” Bateman tells his secretary when he invites her over for the evening.

Online, that message continues to resonate, as social media drives the insatiable hunger for more. In “American Psycho,” Bateman’s identity is a hollow assemblage of labels, products and condescending monologues — a blueprint for the experience of being online today. Like and subscribe to watch the mask slip.