CNN

—

Amid the daily tumult of President Donald Trump’s second term, the political struggles over his economic agenda and his challenges to the basic rules of democracy may seem independent and unconnected. But the outcome of these two fights may converge to a much greater extent than is now apparent.

When it comes to democracy, Trump is moving unrelentingly to seize authority from Congress and the courts and to leverage the massive power of the federal government against an array of institutions (and even individuals) he considers hostile. Though lower courts have blocked several of Trump’s actions, he remains very much on the offense in his drive to expand presidential power and erase democratic safeguards.

On the economy, by contrast, Trump is already playing defense. Polls show that the public is rating his handling of the economy worse than at any point in his first term, and the stock and bond markets and the international value of the dollar have all tumbled since he returned to office. Almost daily, Trump has been forced to backtrack on another aspect of his tariff plans.

The critical question for the coming months may be whether the growing discontent over Trump’s economic performance weakens him politically enough to make Congress members, civil institutions, the courts and the public more willing to resist his efforts to unravel the nation’s small-d democratic safeguards. The more wobbly Trump appears, whatever the cause, the more likely that such institutions will push back against his moves to erode the rule of law.

“The damage he’s done to the economy has also made him more vulnerable to pushback against his efforts to overturn the constitutional system,” said Dartmouth College political scientist Brendan Nyhan, who studies the erosion of democracy worldwide.

Americans have lived through other periods in our history when civil rights, civil liberties and democratic safeguards came under assault. But many legal scholars and historians believe Trump is presenting a threat to the constitutional order unprecedented in its breadth and ferocity. In just weeks, he has taken aggressive actions against law firms and universities; the federal workforce; media organizations; blue states and cities; and individual critics from his first term, all while pushing to the brink of openly defying federal court orders. Several of his targets, from Columbia University to some of the nation’s leading law firms and media institutions, have preemptively capitulated through negotiated concessions.

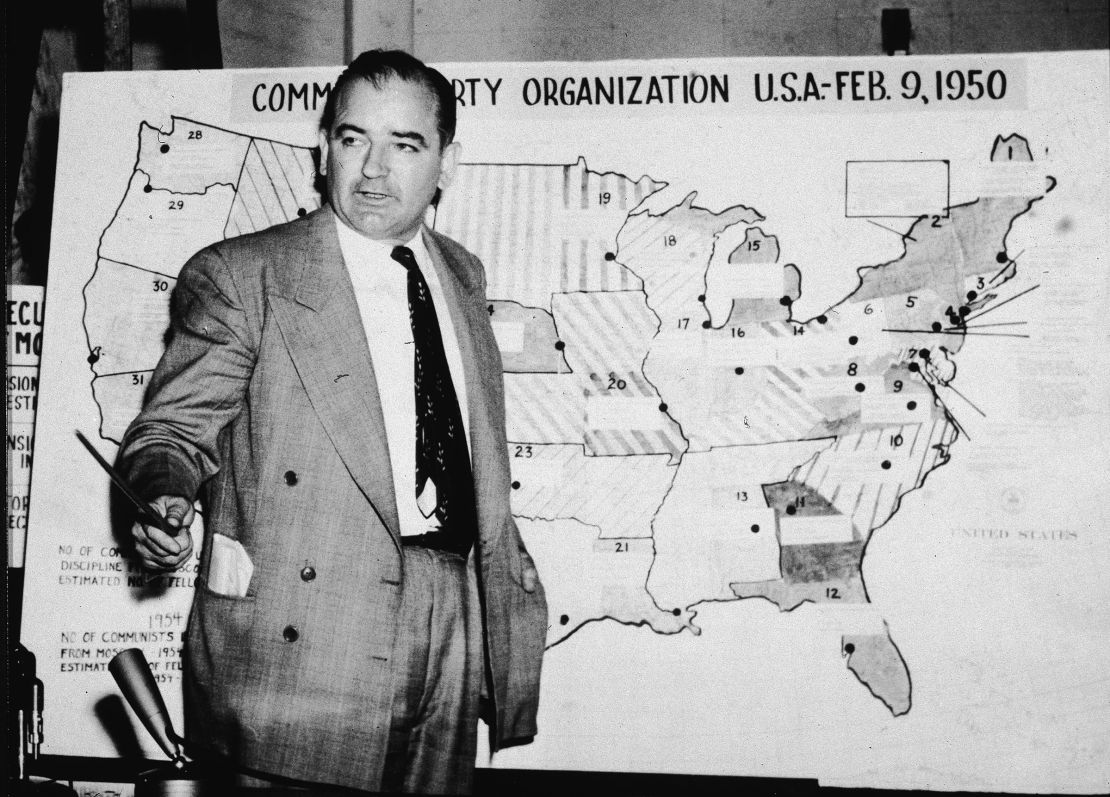

“We’ve never seen anything like this,” said constitutional scholar Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law. “We’ve never seen a situation of a president showing such disregard for the constitution and laws. We can point to things that went on in the (John) Adams presidency or in the Civil War and reconstruction or the (Joe) McCarthy era, but not this number of things or the speed with which they have occurred.”

Litigants and judges have portrayed many of Trump’s actions in nearly apocalyptic terms. Here’s how the NAACP Legal Defense Fund described in a recent brief the implications of Trump’s actions to punish law firms it considers hostile: “If lawyers are forced to pick clients and choose cases out of desire to stay in the Executive Branch’s good graces, the rule of law and the constitutional order it undergirds will crumble.”

Some of these concerns are registering with voters. The flurry of national polls released around Trump’s 100-day mark this week consistently found majorities of Americans agreeing that he is exceeding his legitimate authority as president; in one survey, over three-fifths of Americans said he does not respect the rule of law. Across the various polls, big majorities also indicated opposition to many of the Trump ideas that trouble civil libertarians the most, such as his moves against US universities, his punitive actions against political opponents and his suggestion of incarcerating US citizens in El Salvador.

In these polls, college-educated voters typically express the greatest opposition to these ideas. That concern could help spur higher turnout in elections this year and next among the well-educated, Democratic-leaning voters who already constitute a larger share of the electorate in midterm than presidential years.

Yet in both parties, many are skeptical that large swaths of voters, particularly the less engaged voters who helped put Trump over the top in 2024, will sour on him over the actions that are raising so much alarm among litigants and judges.

For instance, while a majority of Americans in the latest New York Times/Siena poll said Trump was exceeding his powers, slightly less than half said he was doing so in a way that uniquely threatened American democracy. Similarly, in this week’s CNN/SRSS survey, the share who said they had no confidence he will protect Americans’ rights and freedoms came in just below 50%.

Those results suggest that despite Trump’s aggressive and often unprecedented moves, the share of Americans who view him as an existential danger to American democracy hasn’t grown much beyond the coalition that has always perceived him that way.

The president’s “actions that have upset Democrats on rule-of-law grounds are generally actions taken against targets — Ivies, illegal immigrants, Big Law, etc. — that are not beloved by Trump’s base, nor frankly a lot of voters in the center, either,” Republican pollster Kristen Soltis Anderson, a CNN contributor, said in an email.

Jay Campbell, a Democratic pollster, largely agreed. “The most high-profile examples of the erosion of democratic norms don’t have much to do with the daily lives of the vast majority of Americans,” he said. “What does some construction worker in Des Moines care about law firms in Washington, DC?”

Many critics hope that Harvard University’s recent decision to reject the administration’s demands for sweeping changes in its governance and academic practices will mark a turning point toward more systematic opposition to Trump’s pressure campaign. But such a coordinated resistance, despite the exhortation of figures like Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker, still seems remote. Repelling Trump’s agenda to expand his power may feel to his critics like fighting the mythical hydra that grew back two heads whenever one was severed: Seemingly each time a court blocks a Trump action as exceeding his authority, the White House unveils a flurry of new maneuvers designed to shatter the boundaries again.

On the economy, though, Trump is already facing widespread discontent. In Trump’s first term, confidence in his economic management was his most consistent strength, but now, polls from CNN/SRSS, CNBC, Gallup, CBS/YouGov and other pollsters are registering more disapproval of his economic performance than at any point in his first four years.

Initially, polls suggested Americans thought Trump was ignoring the problem of inflation; now surveys suggest many Americans believe he is compounding the problem, particularly with his tariff agenda. In last weekend’s CBS/YouGov survey, more than twice as many Americans said they believed Trump’s agenda was making them worse off financially as said the opposite. Around 60% of Americans consistently oppose his tariffs.

“It is on the economy where his approval has softened, and when you look under the hood, strong approval among Trump voters is down significantly re: the economy,” Anderson wrote.

These numbers could deteriorate further for Trump once price increases and potential shortages on shelves caused by his tariffs become more visible, probably later in May. Congress is also steaming toward votes on a GOP budget plan that would fund large tax cuts that primarily benefit the affluent, most likely by paring back programs that primarily help the middle- and working-class, such as Medicaid. (Trump on Tuesday said advancing that bill would be his top priority for the coming weeks.) That combination has triggered intense public opposition before. While Trump’s ratings on the economy “are bad now,” Campbell said, “they can get to terrible, no question about that.”

While Trump’s critics appear confident about denouncing his economic agenda, they remained divided about how to respond to his challenges to the rule of law.

Two big debates among Trump critics have inhibited that response. One is over political strategy: how much to focus on these threats to democratic norms rather than maintaining a laser focus on the economy. Many of Trump’s actions that most unnerve civil libertarians involve immigration, and some Democrats still fear any fight on that terrain, which they consider Trump’s strongest. (Though that strength may be waning as polls show the public distinguishing between Trump’s performance in securing the border, which most Americans still applaud, and his handling of immigration more broadly, where his ratings have fallen into negative territory.)

To academics who study the decline of democracy worldwide, the Democrats’ indecision ignores the gravity of the stakes. “The congressional Democrats are paralyzed by this search for the perfect message,” said Nyhan. “When the Constitution and the rule of law are under attack, you cannot wait to run on the price of eggs in 2026. Democracy is on the line right now. The Constitution is on the line right now.”

The other dispute is how much to rely on the courts to stop Trump’s actions that threaten democratic safeguards, as opposed to focusing on mobilizing a broad public movement. Legal experts such as Chemerinsky and Georgetown University law school professor David Cole agree that through US history the Supreme Court often has failed precisely at the moments when presidents most threatened the Constitution.

Both see one possible reason for hope in that unsettling history: Usually when the court has allowed a president to retrench civil rights and civil liberties, it’s been during a threat to national security, from the conflict with revolutionary France in the 1790s to the period after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Chemerinsky said he’s encouraged by the precedent that the Supreme Court delivered crucial rulings against President Richard Nixon’s actions against the constitutional system at a time when the security threat wasn’t nearly so great. That same calculation, he says, could influence its choices today. “I don’t think we have a choice but to hope that the courts do this,” Chemerinsky said.

At the opposite end of this debate is Brown University political scientist Corey Brettschneider. When faced with a president intent on retrenching rights, he says, the Supreme Court has frequently compounded the problem — a dubious tradition he sees the current GOP-appointed court majority extending with its 2024 decision virtually immunizing Trump against criminal prosecution for actions in office.

Brettschneider argues that what has worked in the past to stop presidents determined to restrict rights has not been the courts or Congress, but citizen movements such as the anti-slavery movement in the 1850s and the civil rights movement a century later.

“Although we’ve faced moments when the danger from the presidency is there, the thing that has saved us … is movements in which citizens reclaim the Constitution,” said Brettschneider, author of the 2024 book “The Presidents and the People.” If the constitutional system is to survive Trump’s presidency in a recognizable form, Brettschneider argued, the pushback must “be driven by citizens.”

Cole, a former national legal director for the American Civil Liberties Union, said it’s premature to assume even this very conservative court will uphold Trump’s most aggressive actions. But he also believes the courts are less likely to defend democratic guardrails if other institutions are not doing the same.

What American democracy looks like at the end of Trump’s term will depend on “whether people stand up and stand together to push back against blatantly illegal actions of the president,” Cole said. “If we don’t, we cannot expect the courts to save us.”

The responses to Trump’s provocations from the public; major institutions in civil society, local and federal elected officials; and the courts are likely to interact and evolve. But the odds are high that these groups will mostly move in a common direction: toward more capitulation to, or more confrontation with, Trump. Trump’s overall political strength could be pivotal in determining which — and that strength may be measured largely by assessments of his economic performance.

History suggests presidential power is indivisible: Presidents typically don’t gain more control over the debate on some areas of their program while losing leverage on others. A president’s influence tends to simultaneously rise or fall across all issues.

Historians looking back at this era surely will focus less on the price of eggs than on Trump’s systematic effort to loosen the moorings of American democracy. But it may be the price of eggs that determines whether he succeeds.