CNN

—

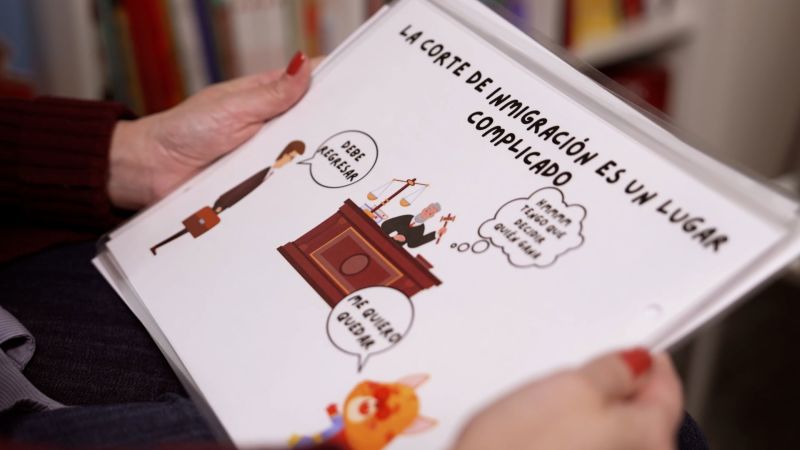

Every week, Evelyn Flores travels to government shelters in the Washington, DC, region for story time with migrant children, telling the tale of a cartoon cat learning to navigate a confusing immigration system with the help of his superhero lawyer.

“They don’t know what is an attorney, they don’t know what is a judge, they are very little,” said Flores, managing paralegal for the children’s program at Amica Center for Immigrant Rights. “We try our best to explain, but it’s so difficult.”

Now, these teachable moments may become even more critical if children are forced to face the courtroom alone, without a lawyer.

Amid public outrage over due process afforded to immigrants, or the lack thereof, it’s some of the youngest in the immigration court system who may be among those hit the hardest by the Trump administration crackdown and funding cutbacks.

The administration decided in March to terminate a federal contract with Acacia Center for Justice, which manages a network of legal service organizations representing around 26,000 unaccompanied children – some who are infants and too young to speak – in the United States.

“This decision was made without any plan in place to address the 26,000 children with open cases that the government encouraged our network to take on. As a result, these children are now unable to meaningfully participate in their cases and are left in the lurch,” said Shaina Aber, executive director of Acacia Center for Justice.

In just the span of a few weeks, the move has resulted in sweeping staff layoffs and a disruption in legal services that could lead to attorneys withdrawing from cases.

“The federal support is everything,” said Wendy Young, president of Kids in Need of Defense. “We would probably see more like 90 percent of these kids going through proceedings without counsel.”

At the same time, migrant children are being placed on expedited court dockets as part of efforts to speed up deportations, significantly cutting the time they have to collect evidence and present their case before an immigration judge.

“This is a process that will just railroad kids through the system,” Young said. “They’ll receive an order to be deported from the United States without any access to due process or fundamental fairness.”

Under US law, immigrants don’t have a right to counsel at the government’s expense, not even children, leaving them to depend on volunteer lawyers or nongovernmental organizations. The Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 created special protections for migrant children, including ensuring “to the greatest extent practicable” that they have counsel to represent them.

The Trump administration has argued in court filings that the federal government has discretion in how it distributes federal funds. “Although, the money was authorized by Congress, Congress never mandated its spending,” it wrote.

A federal judge has since ordered the administration to temporarily restore funding, but to date, that hasn’t happened, according to recipients of those funds.

The Trump administration has said thousands of migrant children who are seeking asylum or other legal status are unaccounted for and is trying to track them down.

“President Trump’s committed to doing everything he can to find these kids, but I’m going to admit to you right now that’s the toughest job of the three things he wants me to do. That’s the toughest part of it,” White House border czar Tom Homan told a special joint session of the Arizona legislature this month.

Experts argue that cutting federal funds for key services runs counter to that effort, taking away the people who are helping them through the immigration system, and that includes reporting to the government.

Flores tells the story of the cartoon cat, known as Fulanito to children 12 years old and under. Fulanito, in Flores’ story time, crosses into the United States and eventually goes before an immigration judge, and his attorney helps him secure immigration relief. For teenagers, the group describes the immigration court process through a soccer analogy.

Organizations who work with migrant children often have to be creative to get them to open up. Staffers use coloring books, fidget toys and stress balls.

“We’ll often color with children. We’ll pull out a page for ourselves and color while we speak with them. It’s hard to talk about heavy things while you’re just staring at each other in the face,” said Scott Bassett, managing attorney of the children’s program at Amica Center for Immigrant Rights.

Young likened her offices to a nursery school. The lesson: how to fight your deportation proceeding.

“We’ll have toddlers running all over the place, and my staff is explaining to them, using toys, crayons, chalkboards, what their rights are in the immigration system. And it’s both something that’s both very poignant, it’s very joyful, but there’s also a tremendous sense of gravity to it,” Young said.

Michigan Immigrant Rights Center, which also works with unaccompanied children, uses handmade toy sets representing a courtroom for one-on-one legal screenings with kids. Kids in Need of Defense puts on puppet shows.

Ages range, but the importance of immigration proceedings remain the same for all who go before an immigration judge – who ultimately decides if someone stays in the United States or is removed.

“I was in a court last summer where a three-year-old was in proceedings. He played with his toy car in the aisle of the courtroom until he was called, and then a young woman picked him up and brought him to the front of the courtroom,” Young said.

“I can tell you, I knew that child knew something dramatic was about to happen. He started crying. He was inconsolable at that point,” she added.

In a recent court filing submitted as part of the ongoing lawsuit over terminating of funds, the Young Center’s child advocates cited “children as young as five years old sitting at tables by themselves in front of judges.”

“During the days immediately following the termination of funding, Child Advocates observed immigration judges learning for the first time at court hearings that funding for legal representation and friend of court services for unaccompanied children had been terminated,” the filings read.

“Upon arriving at court, children also learned for the first time that they would not have an attorney to represent them. In one court, Young Center Child Advocates observed a 14-year-old girl break down in tears in the court’s lobby when she was told that she would not have a lawyer and would need to stand up in court all alone,” it continued.

Releases to guardians slow down and cases speed up

The Health and Human Services Department’s Office of Refugee Resettlement is charged with the care of unaccompanied migrant children until they are released to a sponsor in the United States, such as a relative or family friend.

The agency recently rolled out multiple new policies regarding the release of children to sponsors that make it more difficult for kids to be reunited with their guardians.

Trump officials have argued the additional vetting of sponsors is necessary to ensure the child’s safety. But experts describe it as a dramatic shift that is likely to keep children in custody longer.

“ORR has recently imposed a series of draconian sponsor vetting requirements, including restrictive ID requirements, universal fingerprinting and DNA testing,” said Neha Desai, managing director of children’s human rights and dignity at the National Center for Youth Law.

“This has made it nearly impossible for children in ORR custody to be released if their sponsor is undocumented or if the sponsor lives with people who are undocumented – even if the child is seeking release to their parent,” she added.

Meanwhile, in some courtrooms, cases are being sped up to be resolved in a matter of weeks.

In a New York courtroom on Monday, an immigration judge presided over a group of seven to 10 unaccompanied minors – ranging from ages 6 to 17 and most without legal representation. They appeared virtually from government custody.

The judge guided the children through the basics of the immigration court process.

“Just because you can be removed doesn’t mean you need to be,” Judge Jennifer Durkin told them, emphasizing that their individual stories mattered. She acknowledged the intimidating nature of the proceedings, adding: “My job is to listen to why you came to the United States.”

The minors, who currently reside in a government-run shelter in Brooklyn, appeared attentive. At moments, the seriousness of the hearing gave way to childhood – one boy let out a few playful giggles during the judge’s questioning.

Two children were in the process of reunification with family members. One, a young girl with cerebral palsy who is currently hospitalized, was represented by counsel. Her attorney informed the judge that she was being reunited with her mother.

The six-year-old, the youngest in attendance, was also represented by counsel. His attorney said he was in the process of being reunited with his maternal grandmother.

All the children were scheduled for a second hearing in June or July, giving those without counsel roughly two months to find legal representation.

CNN’s Angelica Franganillo Diaz contributed to this report.