CNN

—

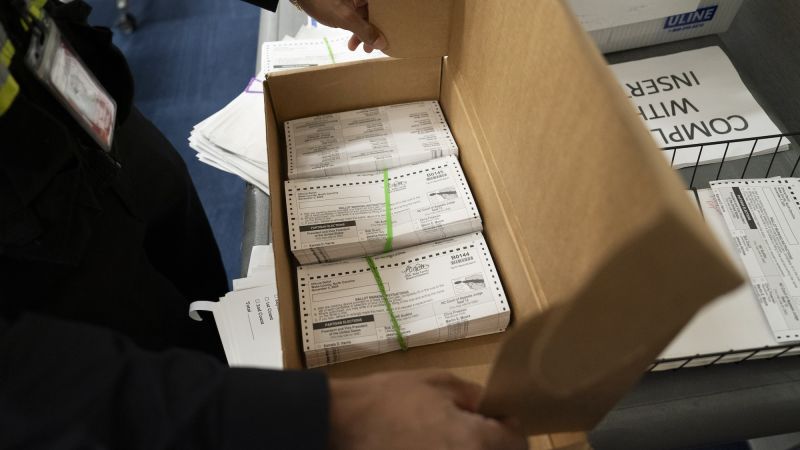

Military families who are deployed far from their homes will see their process for voting become more complex, risking their possible disenfranchisement, with President Donald Trump’s efforts to make certain election policies more stringent.

Trump’s new executive order — which aims to boost proof-of-citizenship requirements and to pressure states to make other changes to their election practices — comes as military voters are already caught in the middle of legal battles over Republican efforts to toss overseas ballots. A Friday court ruling, for example, has jeopardized thousands of overseas ballots cast in a North Carolina Supreme Court race last year.

Trump is now seeking to unilaterally revamp election policies to bring them in line with conservative goals, signing the March executive order that tries to implement policies that Republicans have not been able to achieve legislatively or through the courts.

The military vote has long been seen as sacrosanct politically, and 1986 legislation that sought to clear some obstacles service members face passed with broad bipartisan support. However, the unfounded fixation by Trump and his allies on mass election fraud has translated into efforts that could disenfranchise those serving the nation’s interests abroad.

Critics of the Trump order say members of the military stationed away from their home states may not have easy access to the types of documents the order seeks to require for registering to vote. Even if they do, finding a way to securely transmit those documents to election officials could be difficult. Additionally, Trump is targeting states’ practice of counting mail-in ballots that arrive after Election Day if properly postmarked — a practice that is extended to military and overseas voters in nearly three-dozen states.

“This order just doesn’t take into account our lived experiences and inadvertently creates unnecessary barriers for folks in the military or overseas,” said Sarah Streyder, a military spouse stationed in the United Kingdom and executive directive of the Secure Families Initiative, a military families organization challenging the order in court.

Supporters of Trump’s order say the concerns are overblown.

“When you’re an American abroad, you don’t let your passport out of your sight,” said Hans von Spakovsky, manager of the Election Law Reform Initiative at the Heritage Foundation who is a proponent of such requirements. He argued the Pentagon could also order that the military IDs distributed to service members and their families include citizenship information.

The Defense Department declined to answer CNN’s questions about its plans for implementing Trump’s order.

The White House did not respond to specific questions about the order, but in a statement, spokesperson Anna Kelly said, “President Trump cares deeply about our active duty servicemembers and their families, and he wants to ensure the right of every eligible citizen to vote while preserving election integrity.”

The key provisions of the Uniformed and Overseas Voting Act, or UOCAVA — the 1986 law that eased the process for military and overseas voters — covers both military members abroad and those stationed domestically who need to vote absentee. Not every unformed service member covered under the law would necessarily have a passport.

Trump is seeking to use federal funding and other tools in his arsenal to push states toward his desired election policies. But it is local and state election officials who determine how voting works in their jurisdictions, and the complexities of that state-by-state process is in part why Congress passed the act. The military community accounted for a little less than half of the 1.2 million Americans who were registered under the law in 2020.

Still, 4 out of 5 overseas Americans who did not return a ballot in 2020 said it was because they couldn’t complete the process, according to survey data released by the Defense Department office that helps military families with voting.

“I’ve never heard a single election official have anything but tremendous concern for challenges that those serving American interests overseas might be facing until recently,” said David Becker, a former Justice Department attorney who now leads the Center for Election Innovation & Research, which advises election administrators of both parties.

With his lack of authority over state election registration rules, Trump’s actions to bolster a proof-of-citizenship requirement are aimed at the federal forms that are widely available for Americans to use for voter registration.

Trump directed the Defense Department to add a requirement for documents proving one’s citizenship to the registration postcard that military families and overseas civilians can use to register. His order identifies a short list of documents that would meet the requirement but does not explicitly say that a birth certificate would be enough.

Steyder, of the military families organization, says it shouldn’t be assumed that military families would have an easy time getting their hands on those records, particularly given how chaotic the moving process can be for deployments. State election officials are required to honor the federal postcard application only for a calendar year, and the postcard also must be resubmitted every time the voter moves, Streyder said.

In 2024, her presidential primary ballot was cast from South Korea, her regular primary ballot was cast stateside as she prepared for another move, and her general election ballot was cast from her husband’s current station in the United Kingdom.

“That’s three different postcard applications, three different absentee ballots,” Streyder said.

Overseas voters can use the registration procedures of their home states, but the postcard is supposed to serve as failsafe for those having trouble navigating the process. In 2020, 764,000 voters used the postcard to register — with one-third of those being uniformed service members. That represented a major increase in use over past elections.

Even if those documents are easily at hand, how military voters can submit them to election officials presents its own challenges, since computers and scanners might not be readily accessible where they’re stationed. Streyder raised concerns about security vulnerabilities for transmitting sensitive personal information — particularly for those in roles making them a target — if an overseas voter didn’t have access to a trusted device.

“This can’t be done unless security issues are dealt with,” Becker said. “And so, if there’s not a secure way to send this, it shouldn’t be implemented.”

The most common reason UOCAVA ballots are rejected is that they arrived after a state’s deadline to be counted. Of the ballots cast by military members that were rejected in 2020, almost half were thrown out for that reason. That’s despite federal law requiring election officials send out overseas absentee ballots at least 45 days before an election.

Though UOCAVA doesn’t require it, several states provide overseas and military voters extra time after Election Day for their mail-in ballots to arrive.

The legal challengers to Trump’s order accuse him of putting those ballots at risk as well.

The president exempts UOCAVA ballots from his instruction that the US Election Assistance Commission withhold federal funding from states that count mail-in ballots received after Election Day. But no such exemption exists in a separate, ambiguously worded directive that the attorney general “shall take all necessary action to enforce” an Election Day receipt deadline for mail-in ballots to be counted.

Regardless, von Spakovsky argued the 45 days that UOCAVA provides before Election Day is enough time.

But Streyder said that given the lengthy international mail times, even a highly proactive overseas voter who returns their ballot as soon as they receive it may not see that ballot make it back by Election Day.

Given the limited time absentee military voters already have to make sure their mail-in ballots make it back in time, they “do not have as much time to be maximally deliberative and thoughtful and researched,” particularly when developments in the final weeks of the campaign could change their vote.

“And we have the audacity to believe that that’s not fair either,” she said.

CNN’s Haley Britzky contributed to this story.